wrtitten by Jan Vranken

Just after quarter past eight, Hiromi Uehara stepped onto the stage of the sold-out Muziekgebouw Eindhoven, dressed in a Japanese kimono. The symbolism was unmistakable, yet felt somewhat forced—like seeing Jan Smit perform in traditional Volendam fisherman’s attire in Tokyo. It was the first time the Japanese pianist had visited Eindhoven, opening the So What’s Next Weekend, a three-day jazz festival that profiles itself with boundary-pushing artists. And boundary-pushing is certainly what Hiromi’s Sonicwonder was. The question is: was it going somewhere, or was it merely a demonstration of what’s technically possible?

Hiromi’s Sonicwonder is her third major band incarnation, following Sonicbloom (featuring guitarist David Fiuczynski) and The Trio Project (with bassist Anthony Jackson and drummer Simon Phillips). For this quartet, she has assembled an international dream team: 41-year-old French bassist Hadrien Feraud, compared to Jaco Pastorius by none other than John McLaughlin; 31-year-old trumpeter Adam O’Farrill from the famous Cuban-American jazz dynasty; and drummer Gene Coye from Chicago, a gospel-trained virtuoso with Grammy nominations to his name. After two years of intensive touring and releasing first Sonicwonderland (2023) and now OUT THERE (2025), the band has developed an almost telepathic chemistry.

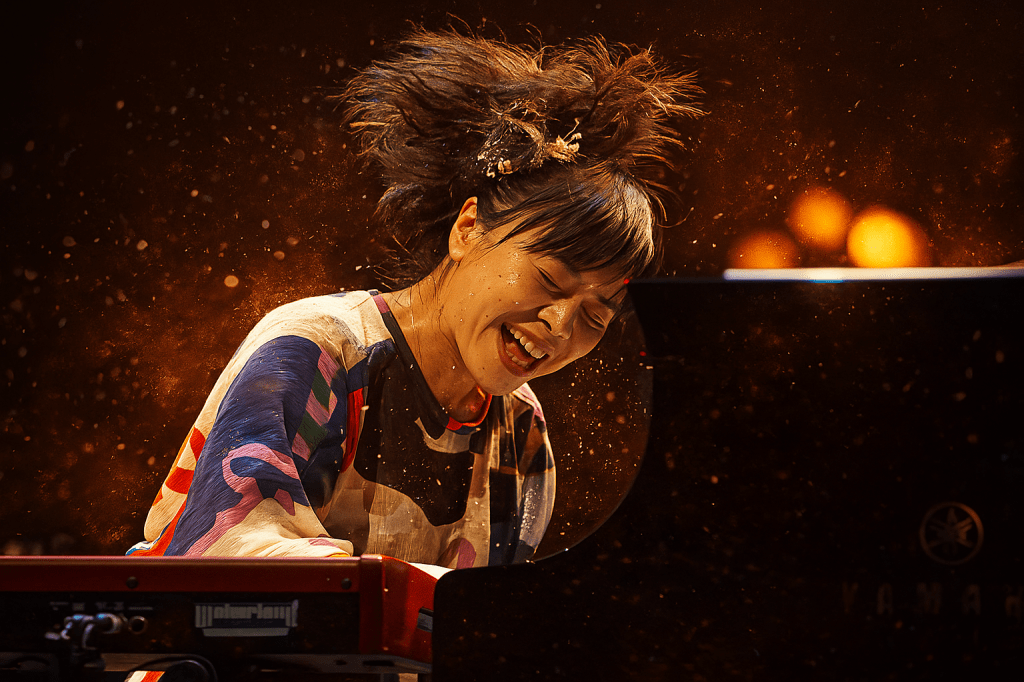

That chemistry was immediately audible when the quartet opened the concert with “Wanted,” the opening track from Sonicwonderland. The moment Hiromi struck the first chords, the entire band snapped into concentration. The audience understood: it’s about to begin. And how. In “Wanted,” a piece in which the bassist can particularly shine, Feraud immediately showed what he was made of, playing spectacularly at a technically high level—a first requirement to even be able to play with Hiromi. What was immediately noticeable: all energy flowed to one point. Hiromi sat on the left side of the stage, but she was the undisputed center. The band focused entirely on her, as if she were a conductor without a baton.

Adam O’Farrill, who in his own work as a bandleader (Stranger Days, ELEPHANT) seeks space and cinematic quality, transformed into a completely different musician in Hiromi’s context. His trumpet sound, heavily processed with digital distortion and effects pedals, brought unexpected colors—sometimes almost synthetic, other times raw and organic. It was refreshing to hear how he adapted to Hiromi’s sonic universe without losing his own voice.

But the real star of the evening? Drummer Gene Coye. While others on stage were mainly occupied with power and speed, Coye was the one who made the music breathe. On a regular acoustic drum set—no pads, no electronics, just those blazing rimshots that got an extra treatment on the mixing board—he played with a fluidity reminiscent of Tony Williams. Pure from the wrists, without abusing force, with subtlety on the hi-hat. He was the anchor, the warm musician in an otherwise often cool-sounding ensemble.

Because that’s also immediately where the friction of this evening lies. Hiromi Uehara is a technical phenomenon, a pianist whose fingers reach speeds that border on the inhuman. Since her breakthrough in 2003 with Another Mind, her mentorship under Ahmad Jamal and Chick Corea, and her Grammy-winning collaboration with Stanley Clarke, she has proven herself as one of the most explosive performers in the jazz world. She performed at the opening ceremony of the Tokyo Olympics in 2021. She composed the soundtrack for the anime film Blue Giant. She is, in short, a titan.

But greatness can also overwhelm instead of move. Hiromi plays as if she has an automatic impact drill screwed onto her wrists. Impressive, certainly. But touch-sensitive keyboards are wasted on her. The dynamics are one-sided. Subtlety and softness? You’ll search for them in vain in her playing. Where Coye brought space, Hiromi filled every second with notes—as if silence were an enemy that must be defeated.

The second number, the title track “Sonic Wonderland,” lasted almost ten minutes and was pure fusion as it’s meant to be: rooted in the tradition of Weather Report and Return to Forever, but with those typical bubblegum keyboard sounds that Hiromi loves so much. The audience was left stunned. Hiromi danced behind her instruments in her kimono, energy leaping from the stage. And yet you couldn’t shake the feeling: is this just another day at the office for them? They smiled, they enjoyed themselves, but it didn’t seem to be a special evening for the quartet themselves. Adequate, self-assured, perfectly executed.

After a good half hour, Hiromi introduced the band and announced that the rest of the evening would be devoted to the complete performance of the OUT THERE suite: “Takin’ Off,” “Strollin’,” “Orion,” and “The Quest.” Without interruption, without further commentary. What followed was an exhilarating three-quarters of an hour in which the audience was completely overwhelmed by such technical prowess. The suite is ambitious: a four-part composition that weaves together jazz-fusion, prog-rock, funk, and even disco. “Takin’ Off” opened with a rapid-fire melody, Feraud and Hiromi became entangled in a call-and-response that resembled a Formula 1 race on their instruments more than a conversation. “Strollin’” brought a nod to the ’70s fusion of Herbie Hancock and George Duke.

And then “Orion”—finally, the musical highlight of the evening. Here the pace was pulled back, here the enormous musicality of the musicians came to the fore. O’Farrill played with muted trumpet, Hiromi chose mostly acoustic piano over electronics, and Coye laid down a subtle rhythmic carpet on which the melody could float. This was the moment when technique seemed to make way for feeling, when perfection offered space for expression. “The Quest” concluded with an energetic start-stop rhythm and synth sounds that seemed to come straight from the prog-rock archives. It was spectacular, no doubt about it. But it also came eerily close to the album version. Few surprises, little improvisation outside the beaten path. The live sound and the studio sound were so close together that you wondered: why would you attend this concert if you could put on the record at home?

The Eindhoven audience gave a standing ovation, and it was deserved. This was craftsmanship of the highest level. But a standing ovation can mean different things. It can be admiration, or gratitude, or even bewilderment. And bewilderment seemed the right word here. People were impressed by the technical level, but that moment of real connection—where energy flows between stage and hall, where you as a spectator become happy—that was missing. Hiromi barely spoke, explained nothing, shared no stories. It was as if the music had to speak for itself, but music that is so complex sometimes calls for a human link.

This is not a lack of respect for what was presented here. On the contrary. The Muziekgebouw Eindhoven deserves all praise for programming this music, for offering space to boundary-pushing jazz in a time when many venues opt for safer choices. And Hiromi’s Sonicwonder is unmistakably a world-class band. But perfection can also be a cage. Sometimes the most beautiful thing about live music is not what goes right, but what happens when there’s room for the unexpected, for the mistake, for the silence.

Gene Coye understood that. He was the warm heart in an otherwise cool machine. The rest of the band delivered a demonstration of what’s technically possible in contemporary jazz-fusion. Whether that’s enough depends on what you’re looking for. Do you want virtuosity and precision? Then this was your evening. Are you looking for a moment of magic, of connection, of surprise? Then Hiromi’s Sonicwonder remained still out there—somewhere in space, just beyond reach.

Photo”s Copyright Jan Vranken

Plaats een reactie