Written by :Jan Vranken

As voters cast ballots today, a pop star faces off against Africa’s longest-serving strongman in an election that reveals how autocracy adapts—and why simply surviving can be victory

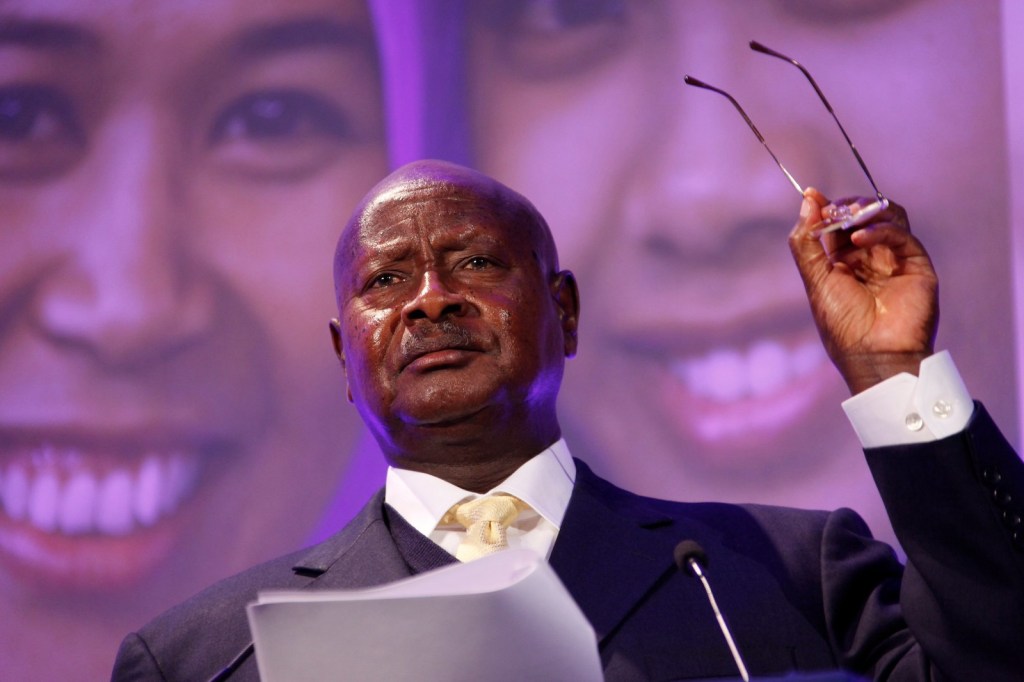

Kampala, Uganda — Ugandans headed to polling stations today under internet blackout and heavy military deployment as 81-year-old President Yosef Museveni seeks to extend his 39-year grip on power against the charismatic musician-turned-opposition leader Bobi Wine, 43.

For Europeans watching from afar, this may look like just another African election between an aging dictator and a youthful challenger. But to understand what’s truly at stake requires grasping uncomfortable truths about how Museveni’s Uganda has shaped—and continues to destabilize—an entire region through violence that reaches back to the Rwandan genocide and forward to wars that killed millions in Congo.

The Strongman Who Built His Power on Other People’s Wars

Yosef Museveni didn’t rise through elections. He fought his way to the presidential palace in 1986 after a five-year guerrilla war. For a decade afterward, Western governments celebrated him as part of a “new generation of African leaders” bringing stability and economic reform.

That narrative obscures a darker reality: Museveni has been a primary architect of regional violence for nearly four decades.

The Rwanda Connection: When Rwanda’s Tutsi-led Rwandan Patriotic Front invaded in 1990 and eventually stopped the 1994 genocide, it did so from Ugandan soil with Museveni’s explicit support. The relationship between Museveni and Rwanda’s Paul Kagame runs deep—both were guerrilla allies in the 1980s, with a third of Museveni’s rebel army during Uganda’s civil war composed of Rwandan refugees.

But this wasn’t humanitarian intervention. It was the beginning of a pattern.

The Congo Wars: Between 1996 and 2003, Uganda became a primary actor in what some call “Africa’s World War”—the conflicts in the Democratic Republic of Congo that killed an estimated 5.4 million people. Uganda and Rwanda together sponsored rebel movements, first to overthrow Mobutu Sese Seko in 1996-97, then launching a second invasion in 1998 when the new Congolese president turned against his former patrons.

UN investigators documented systematic looting of Congolese gold, diamonds, and timber by Ugandan military officers. In 1999-2000, Ugandan and Rwandan soldiers even fought each other in the Congolese city of Kisangani, resulting in around 3,000 civilian deaths and 1,000 military casualties. Uganda would later be handed a $10 billion reparations fine by the International Court of Justice.

The pattern continues today: Rwandan forces backing the M23 rebel group captured the eastern Congolese city of Goma in early 2025, with UN investigations finding evidence that M23 also receives support from Uganda.

The Child Soldier Horror: For over two decades, northern Uganda endured a brutal insurgency by Joseph Kony’s Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA). The LRA became internationally notorious for abducting an estimated 25,000 to 66,000 children, forcing them to become soldiers and sex slaves.

What Western media rarely discussed: the war devastated the Acholi people of northern Uganda—an ethnic group that had supported previous regimes and remained suspicious of Museveni’s southern-dominated government. By 2006, nearly 95 percent of the Acholi population had been displaced into camps with some of the highest mortality rates in the world.

Critics argue Museveni deliberately prolonged the conflict, refusing peace negotiations that might have ended the LRA insurgency years earlier, because the war kept the north marginalized and dependent on military protection. The government’s response included a scorched-earth policy forcing all Acholis into “protected villages” beginning in 1996, camps that World Health Organization data indicated caused ten times as many deaths as the LRA itself.

This is the man seeking his seventh term today.

The Musician Who Refuses to Disappear

Robert Kyagulanyi Ssentamu—Bobi Wine—grew up in Kamwokya, one of Kampala’s toughest slums. His music career gave voice to Uganda’s frustrated youth: unemployment, corruption, police brutality, a gerontocracy controlling all power.

In 2017, he made an unusual move: running for parliament not as a celebrity seeking new attention, but as an activist transforming his musical following into political mobilization.

In 2021, he challenged Museveni directly, officially receiving 35 percent to Museveni’s 58 percent—the president’s poorest margin since taking power. International observers documented widespread irregularities: internet shutdowns, opposition candidates blocked from campaigning, vote tallying in secret, independent monitors denied access.

Scores were killed in violence around the vote, Wine was shot at, arrested, and allegedly tortured. His driver was shot dead—Wine claims the bullet was meant for him.

This time, the pattern repeats with escalation. Wine now rarely appears in public without a flak jacket and helmet, having been beaten, tasered, and attacked with tear gas while campaigning. In October and November 2025, at least 95 opposition members were arrested or charged with minor offenses. In December, Wine and supporters were attacked and beaten by security forces in Gulu.

Voting takes place today under internet blackout, with Uganda’s Communications Commission citing “misinformation, disinformation, electoral fraud” as justification—though pro-democracy activists note the blackout prevents them from documenting ballot stuffing and irregularities.

Another leading opposition figure, Kizza Besigye, remains in jail after being seized from neighboring Kenya in November, charged with treason.

Why Survival Is the Real Victory

Here’s what European observers must understand: Bobi Wine will almost certainly not win this election. If somehow he did, Museveni would not accept it.

But that’s not the point.

Wine’s appeal taps into a generational reality: with a median age of 16, most Ugandans judge the regime not by its 1980s “liberation narrative” but by today’s hardships—unemployment, corruption, poor public services.

Uganda has never experienced a peaceful transfer of power between elected leaders since gaining independence. An overwhelming majority of its 50 million people are under 40 and have only ever known one president.

In entrenched authoritarian systems, opposition leaders serve functions beyond electoral victory. They maintain the idea that alternatives exist. They train new activists. They create networks that survive crackdowns. They demonstrate, simply by continuing to speak and breathe, that the regime is not inevitable or eternal.

Museveni is 81. His son Muhoozi Kainerugaba, the country’s top military commander, is widely seen as his heir. Muhoozi infamously threatened to put Wine to death in a January 2025 social media post. Analysts note two scenarios: Muhoozi could work within the system, allowing for political competition that protects Uganda’s limited democratic gains, or he could seek a quicker route to power, potentially through military takeover.

Every year Wine survives, every election he contests, every speech he gives normalizes the idea that Ugandans deserve better than a president-for-life with blood on his hands from Kampala to Kinshasa.

The Tribal Trap Europeans Don’t Understand

To grasp Wine’s challenge requires understanding something that doesn’t translate to European political frameworks: Uganda is not a nation-state in the Western sense. It’s a British colonial invention stitching together dozens of distinct ethnic groups and several pre-existing kingdoms.

The largest kingdom, Buganda, was restored as a constitutional monarchy in 1993. Its king, the Kabaka, holds no official political power but commands deep loyalty from the Baganda people—roughly 16 percent of Uganda’s population, concentrated around Kampala.

Think of it like this: imagine if the UK still had functioning Anglo-Saxon kingdoms alongside modern democratic government, and the King of Wessex could influence millions of votes through cultural authority despite holding no office.

In 2021, Wine swept Buganda and Busoga regions. His detractors immediately claimed he was merely a tribal leader recognized only among Baganda, deriding his National Unity Platform as a revival of Kabaka Yekka, a defunct party advocating Ganda nationalism in the 1960s.

This creates Wine’s paradox: He is a proud Muganda but no ethnic chauvinist—his urban upbringing gives him a cosmopolitan outlook. Even critics acknowledge his “detribalized” instincts and intellectual bent. Yet his party won 56 of its 58 parliamentary seats in Buganda, making it easy for opponents to paint NUP as narrow regional politics.

The Kabaka of Buganda has remained studiously neutral, refusing to openly endorse Wine. Past kings were exiled when they opposed government too directly. The current Kabaka walks a careful line, protecting the kingdom’s cultural autonomy by not threatening Museveni’s political dominance.

Meanwhile, in northern Uganda—still recovering from the LRA war that killed an estimated 100,000 civilians and displaced 1.9 million people—some voters remain suspicious of southern candidates and Baganda politicians specifically, given historical tensions.

This is what Wine must navigate: building a truly national coalition in a country where “national” politics fractures along ethnic and regional lines, and where traditional authorities influence constituencies without formally entering politics.

What Europeans Should Understand

As results come in today—almost certainly declaring another Museveni victory amid opposition allegations of fraud—the story isn’t really about who wins.

It’s about whether systems of repression can be sustained indefinitely, or whether persistent opposition creates cracks that eventually widen.

It’s about whether the international community will continue treating Uganda as a “stable partner” while ignoring that this stability rests on regional military interventions, mass displacement of ethnic minorities, and systematic electoral manipulation.

And it’s about recognizing that in places where democracy has been strangled for decades, the act of surviving to contest another day—of maintaining visible, vocal opposition despite arrests, beatings, and threats—is itself a form of political victory.

“It is important for us to challenge the authoritarian leader—again and again—until we eventually get our freedom,” Wine told CNN. “Because not challenging him means giving up”.

Today’s vote is not the end of Uganda’s democratic struggle. It’s barely the beginning. But as long as Bobi Wine walks out tomorrow still speaking, still organizing, still alive—that represents something authoritarian regimes can never fully suppress.

In the long African political tradition, that persistent visibility is often how the impossible eventually becomes inevitable. Whether it takes five years or fifteen, whether it comes through Wine or someone who follows him, Museveni’s era—like that of all strongmen—will end.

The question is what Uganda becomes afterward, and whether the democratic infrastructure Wine is building today survives to shape that transition.

That’s why this election matters—not for who wins, but for who endures.

Plaats een reactie