Written by : Jan Vranken

Somewhere in heaven’s jazz clubs, Fela Anikulapo Kuti must have raised his fist when the Grammys awarded him their Lifetime Achievement Award posthumously last week. “You see, I got them now, I got their attention!” he would have shouted, as his album cover designer Lemi Ghariokwu imagines. But would that fist have been raised in triumph or in protest?

Because here lies 2026’s ultimate paradox: the man who sang in “Colonial Mentality” (1977) about the African inferiority complex toward the West, “de ting wey black no good, na foreign things them dey like,” is now being celebrated by precisely that Western establishment he fought his entire life. Twenty-nine years after his death, Fela Kuti is the first African to receive the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award. Better late than never? Or better never than this late?

The timing couldn’t be more ironic. While the Recording Academy finally embraces the father of Afrobeat, the continent he fought for is selling itself to the highest bidder at record speed. China’s Belt and Road Initiative is redrawing Africa’s infrastructure, American tech giants are racing for critical minerals, and the old colonial powers are suddenly rediscovering their “strategic interests.” The pan-Africanism Fela lived for, and nearly died for when 1,000 Nigerian soldiers burned down his Kalakuta Republic in 1977 and threw his mother out a window, seems like a museum piece from a more idealistic era.

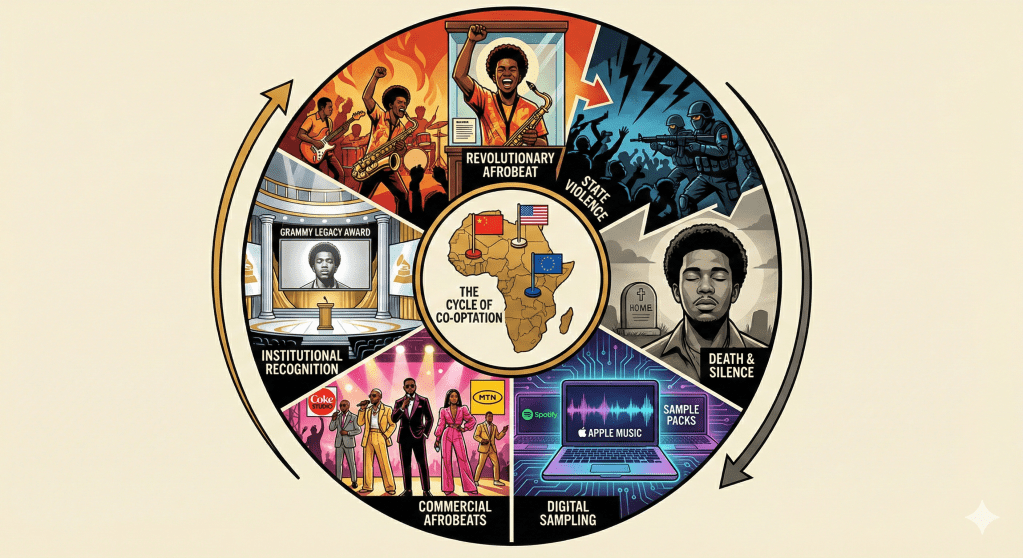

And yet. When Burna Boy and Wizkid sample Fela’s DNA for Billboard hits, when Beyoncé and Paul McCartney praise his influence, when his grandson Made brings in the family’s eighth Grammy nomination, what remains of the revolution? Is this the victory Fela meant, or is it proof that the system always wins by posthumously canonizing rebels?

The question nobody dared ask at the Los Angeles ceremony: would Fela have accepted this award at all?

From Kalakuta Republic to Lagos Swing, But For Whom Does This Door Open?

This is where the story gets really interesting. Because let’s be honest: Fela’s Grammy comes at the moment when Afrobeats, note the “s,” has become commercially unbeatable. Burna Boy sells out Madison Square Garden, Wizkid dominates streaming charts, Tyla wins her second Grammy. The establishment has made its peace with the beat, as long as it’s danceable and exportable.

But what happens to the artists who continue Fela’s spirit instead of just sampling his sound?

The Cavemen are doing with their “Lagos Swing” exactly what Fela did in the sixties: fusing Nigerian roots, highlife, with jazz, funk, and a political consciousness that goes beyond Instagram activism. Their debut “Roots” (2020) and “Love & Highlife” (2022) are a masterclass in cultural authenticity without falling into nostalgia. They play live instruments in an era of producers and laptops. They sing in pidgin and Yoruba when it would be easier to choose English hooks. They are precisely what the Grammys claim to want to honor in Fela, but don’t even get a nomination.

Little Simz, okay, she has a Mercury Prize and critical acclaim, but how much Grammy attention does a British-Nigerian woman who makes albums like “Sometimes I Might Be Introvert” get? Music that’s political without slogans, African without clichés, complex without being arrogant. Would Fela’s award smooth her path, or will the Grammy machine remain focused on what’s already proven commercially viable?

Pa Salieu brings his Gambian-British experience with an urgency that Fela would recognize, the voice of displacement, of systemic struggle, of a generation balancing between continents and identities. “Afrikan Rebel” (2024) should stand alongside the Afrobeats giants in a just world. But will he get that chance now that Fela has been “accepted”?

And then Obongjayar, perhaps the most fascinating of the lot. His experimental, genre-refusing approach on “Some Nights I Dream of Doors” (2022) is precisely the kind of artistic freedom Fela fought for. But “experimental” and “Grammy” rarely go hand in hand, unless you’re called Radiohead and you’re white.

Here’s the bitter truth: Fela’s award doesn’t come because the Grammys finally want to honor alternative African voices. It comes because Afrobeats is now too big to ignore, and Fela posthumously is a safe way to appear “progressive” without taking risks. The question isn’t whether the Recording Academy has recognized Fela, the question is whether they’re willing to recognize the living artists who actually continue his rebellion, his experimental drive, his refusal to bend to the market.

Because let’s be real: a Lifetime Achievement Award for a man who’s been dead for 29 years isn’t a statement. It’s historiography. It’s safe. Fela can no longer give an awkward acceptance speech, can’t use a Grammy podium to denounce colonialism, can’t make soldiers nervous anymore.

The real test comes now: will this recognition open the door for The Cavemen’s next album? Will Obongjayar finally get the international attention his work deserves? Will Pa Salieu’s Gambian diaspora story be considered as important as the next Wizkid hit?

Or will it remain symbolic, a Grammy for a dead revolutionary, while the living revolutionaries still stand waiting outside?

Pan-Africanism is Dead. Long Live the Export.

Let’s stop the romance and look at what’s really happening.

When Fela tried to run for president of Nigeria in 1979, he did so from an ideology that now sounds almost naive: Africa for Africans. No neocolonial interference, no Western cultural hegemony, no sellout of resources and sovereignty. He wanted a continent that owned itself, in every sense of the word.

Grab a map today. Look at the Chinese mining concessions in the Democratic Republic of Congo, 80 percent of the world’s cobalt, essential for every Tesla, every iPhone, every green transition the West preaches. China pays, China digs, China exports. The Belt and Road Initiative now has more than 40 African countries in its web. Debt trap? Neocolonialism with Chinese characteristics? Doesn’t matter, the contracts are signed, the ports are being built, the dependency has been created.

And the West? They’re playing the same game, just with better PR. “Strategic partnerships.” “Development aid.” “Critical mineral security.” Translation: we need your lithium, your coltan, your uranium for our energy transition, and we pay just enough not to look like the bad guys.

Here’s the humiliating truth: the continent Fela fought for no longer exists. Or rather, it never existed outside the dream. Because while Fela was singing “Colonial Mentality,” Nigerian elites had been busy robbing their own country blind for decades. The enemy wasn’t only in London or Washington. It was also in Lagos, in Abuja, in every regional capital where postcolonial leaders perfectly adopted colonial structures to enrich themselves.

And the music? Afrobeats is now a $2.3 billion industry. Export product number one. Spotify playlists, luxury brand collaborations, festival headliners worldwide. Beautiful, right? African artists finally getting what they deserve?

But listen closely to the lyrics.

Where Fela wrote “Zombie,” a frontal assault on the Nigerian army that nearly cost him his life, the average Afrobeats hit sings about champagne, designer clothes, and “making it.” Where Fela made “Shuffering and Shmiling” about religious hypocrisy and economic exploitation, you now hear hooks about “shayo” and “gbedu.” Where Fela used every album as a political pamphlet, the modern Afrobeats hit is optimally optimized for TikTok virality and brand partnerships.

This isn’t criticism of individual artists. This is observation of a system. Capitalism has learned how to sell revolution without the revolution. You take the beat, the aesthetics, the cultural pride, and you filter out every political edge. The result is perfectly exportable, perfectly consumable, perfectly harmless.

Burna Boy calls himself “African Giant,” and rightfully so, his talent is undisputed. But when was the last time an Afrobeats mega-hit attacked a concrete government, exposed a specific injustice, took an actual risk? Fela was arrested, beaten, his compound was burned down. Modern Afrobeats stars are sponsored by telecom giants and crypto companies.

And now the Grammys give Fela a Lifetime Achievement Award.

See the perfect circle? The establishment Fela fought canonizes him posthumously. They make him “legacy,” museum piece, historical footnote. Safe. Temporized. No longer a threat. And meanwhile they continue to ignore the living artists who continue his spirit, because those are unpredictable. Those can still say something that makes shareholders nervous.

The Cavemen play instruments in an era of MIDI. Obongjayar makes music that doesn’t fit in playlists. Pa Salieu raps about displacement and systemic failure. Little Simz refuses to bend. These are the heirs of Fela’s ethos, but they’re not commercial enough, not “accessible” enough, not safe enough for mainstream recognition.

So the question remains: is this Grammy a victory for Africa, as Femi Kuti claims? Or is it the definitive proof that the system always wins, not by stopping dissidents, but by posthumously incorporating them into the canon, thereby turning their rebellion into historical curiosa instead of current threat?

Fela sang “Teacher Don’t Teach Me Nonsense” in 1986. Forty years later he gets an award from people who fundamentally haven’t understood his lesson, or worse, have perfectly understood it and therefore wait until he’s safely dead.

Pan-Africanism hasn’t died. It’s been bought, packaged, and resold as a lifestyle brand. And the Grammy for Fela? That’s the receipt.

Or Worse: Senegal Sells Its Sea for a Football Stadium

Let’s make it even more concrete. Because this isn’t about abstract geopolitics. This is about fishermen in Kayar, Mbour, Saint-Louis who go out to sea and come back with empty nets.

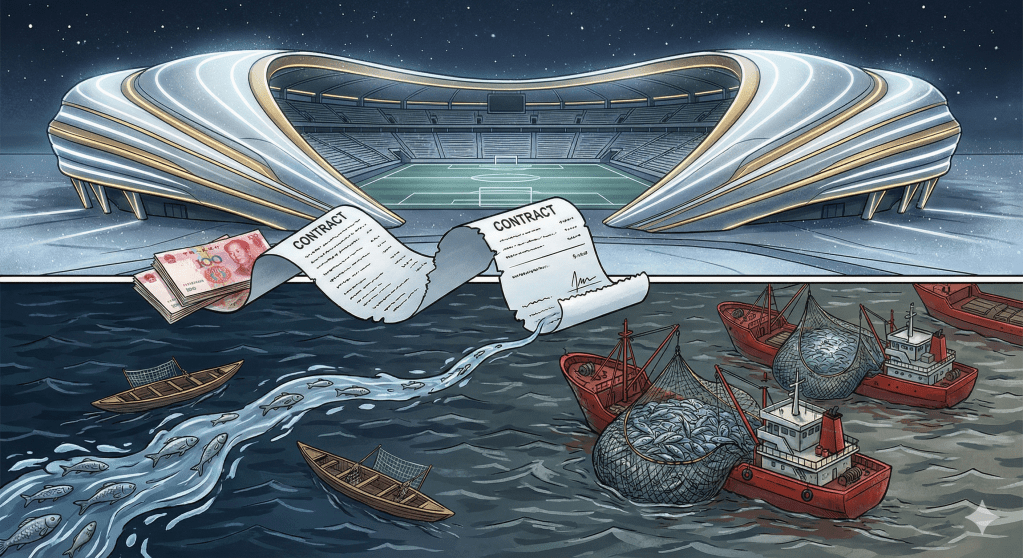

China has bought the fishing rights for the West African coast. Senegal, the country Fela would have seen as a brother nation in the pan-African struggle, is selling access to its waters. The deal? A shiny new football stadium. Capacity: 50,000. Cost: $238 million, financed by China. The price: the future of Senegalese fishing.

Every day, Chinese industrial trawlers sail along the Senegalese coast. Factory ships with nets so large they can haul in entire schools of fish in one sweep. They’re fishing for the same terracotta that for centuries was the protein source for West African communities. The local fishermen, with their pirogues and hand-thrown nets, can’t compete. Fish prices rise. Food security falls. Young men see no future and take those same pirogues to make the life-threatening crossing to the Canary Islands.

But hey, nice stadium though.

This isn’t an exception. This is the pattern. Congo sells cobalt mines for infrastructure that Chinese companies build with Chinese workers. Zambia mortgages its copper mines for loans it can never repay. Ethiopia gives away agricultural land to Saudi Arabia and India while millions of its own citizens need food aid. Djibouti has practically handed its strategic port to Chinese control, 70 percent of state debt repayments go directly to Beijing.

And the worst part? This happens with the consent of African governments. This isn’t colonialism that requires an army. This is colonialism that only requires a checkbook and local elites willing to sell their country for personal enrichment and prestige projects.

Fela would vomit.

He sang “Teacher Don’t Teach Me Nonsense” and “Authority Stealing” about precisely this mechanism. The way African leaders, freed from colonial rule, immediately continued the same extractive structures. He saw it in the seventies and eighties. It’s only become more refined. The colonial governor has been replaced by the CEO. The soldiers by consultants. But the outcome is the same: Africa’s wealth flows outward, and what comes back is debt, dependency, and occasionally a football stadium for show.

And now the West gives Fela a Grammy.

The same structures he fought, Western cultural hegemony, economic exploitation, the reduction of African culture to export product, give him a posthumous pat on the head. “Well done, old man. Beautiful music. Very inspiring. Here’s your award. We’ve finally categorized and catalogued you. You’re safe now.”

Meanwhile the Chinese trawlers keep fishing. The debt burden grows. The minerals are exported. The profits flow to Shanghai, to New York, to London. And young Senegalese fishermen drown in the Atlantic Ocean searching for a future their own governments sold them for a stadium they can’t afford a ticket to.

This is the world in which Fela’s Grammy is awarded.

A world where his music is celebrated, but his message is ignored. Where Afrobeats megastars perform at corporate events sponsored by the same multinationals that are bleeding Africa dry. Where “African pride” has become a marketing term, perfectly optimized for streaming algorithms and luxury brand collaborations.

The fishing rights are sold. The football stadium stands. The Grammys have recognized Fela. And everyone pretends this is progress.

Fela as Looted Art: Or How to Posthumously Colonize a Revolutionary

The British Museum is finally, after 200 years, returning certain art treasures to Egypt. Not all, of course. Not without conditions. And certainly not without years of international pressure, diplomatic negotiations, and the uncomfortable realization that the world no longer accepts that stolen goods “preserved for humanity” means “preserved in London for British institutions.”

The Benin Bronzes? Back to Nigeria, but only on loan first, you understand. The Rosetta Stone? We’re still talking about that. The Parthenon Marbles? Ah, well, that’s complicated, you know.

The same logic is now playing out with Fela.

He’s not being recognized. He’s being repatriated. Posthumously. On conditions. And most bitterly: by precisely the institutions that tried to ignore his music as long as he could still fight back.

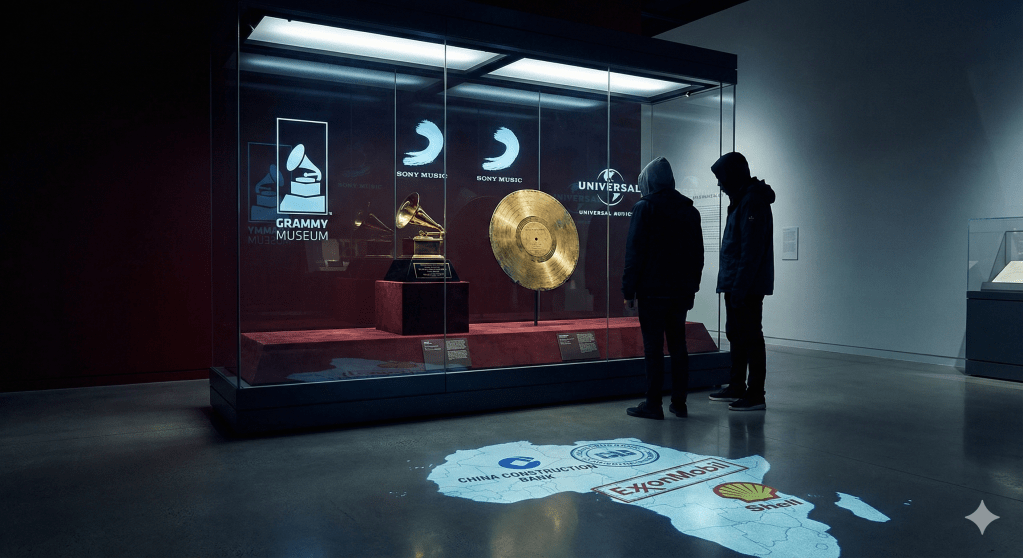

Think about it: the British Museum looted African art, placed it in climate-controlled vitrines, and told the world they were “protecting it” and “making it accessible for educational purposes.” The fact that it was stolen, that it lost context, that it became part of an imperialist narrative, those were details. What mattered was that London now determined what was important, how it was presented, what it meant.

The Grammys are now doing exactly the same thing with Fela.

They take a man who fought the Western establishment, who was arrested, tortured, whose mother was murdered by the state, who refused to conform to any music industry logic whatsoever, and they place him in their vitrine. “Lifetime Achievement Award.” Nice label. Neatly categorized. “World Music” section, naturally. Made accessible to a new audience. Educational value. Legacy preservation.

But just as the Benin Bronzes lost their meaning when they were ripped from their context and displayed in Bloomsbury, Fela’s rebellion loses its power when it’s curated by the Recording Academy.

Because here’s what they do.

They recognize Fela’s “influence on Beyoncé, Paul McCartney, and Thom Yorke.” Perfect whitewashing. His value is measured by which Western artists he inspired. Just as African art in the British Museum is presented by emphasizing how it influenced European artists. Picasso and his African masks, you know. Not the meaning of those masks themselves, not the cultures that created them, but how white talent was helped by them.

They celebrate his “creation of Afrobeat,” as if it were a genre instead of a political statement. As if it was about the beat and not about the message. They strip out the politics and keep the aesthetics. Precisely what you do with looted art: remove the spiritual meaning, neutralize the contextual power, and only retain the physical beauty that can be safely displayed.

They give him an award 29 years after his death. Just as the British Museum only returns art when the pressure becomes too great and the original owners are dead anyway. Return what you can no longer hold without losing face, but only do it when it’s safe. When there’s no living voice left that can hijack the podium to say what he really thought of your institutions.

And most perverse of all: just as the British Museum now determines how and when looted art is returned, only on loan first, only certain pieces, only on our conditions, the Grammys now determine how Fela is remembered. They write his legacy. They determine his narrative. They curate his rebellion into something that fits within their framework.

“Fela Kuti: Pioneer of Afrobeat, Inspiration to Global Artists, Lifetime Achievement Award 2026.”

Not: “Fela Kuti: Anti-Imperialist Activist, Political Prisoner, Man Who Fought Your System Until His Death and Whose Mother Was Murdered By Precisely The Type of State Violence Your Industry Has Always Ignored.”

That doesn’t fit the plaque. That’s not museum-worthy. That disrupts the aesthetics.

Senegal sells fishing rights for a stadium. The British Museum keeps the Rosetta Stone. The Grammys give Fela an award.

All the same logic: we take what we want, when we want, how we want. And later, much later, when the pressure becomes too great or it’s PR-favorable, we give something back. But always on our terms. Always in our context. Always in a way that confirms our power instead of undermining it.

Fela is now looted art.

Safe behind glass. Perfectly lit. With an information board explaining why he’s important, written by people who never understood him, or worse, understood him perfectly and therefore waited until he was dead.

And in 50 years they will perhaps, perhaps, under pressure, with great reluctance, recognize a few living artists who continue his spirit. The Cavemen, Obongjayar, Pa Salieu, if they’re lucky and survive long enough and the cultural zeitgeist has changed and it’s become commercially safe.

Or they’ll just wait until those are dead too.

Safer that way.

The Dead Cannot Fight Back

So here we are.

Fela Kuti, who survived 1,000 soldiers, who saw his mother die from state violence, who was arrested time and again because his music was too dangerous, who refused to bow to any establishment whatsoever, gets a posthumous pat on the head from precisely that establishment.

And we pretend this is a victory.

“Finally recognition for Africa!” we cheer. While Chinese trawlers are emptying the Senegalese coast right now. While Congolese children crawl in cobalt mines so we can drive electric. While African governments sell their sovereignty for football stadiums and highways leading to ports where resources are exported.

“Fela’s legacy lives!” we write. While the artists who continue his spirit, who play instruments, who dare to be political, who refuse to bend to algorithms and brand partnerships, don’t even make the shortlist.

Because here’s the truth nobody wants to say: this Grammy isn’t recognition. It’s a funeral. It’s confirmation that Fela is now safely dead enough to be celebrated. That his rebellion can be historicized. That his music can be categorized without anyone having to be nervous about what he would say now.

About the fishing deals. About the mining concessions. About how Afrobeats kept the beat but sold the revolution. About how his own continent betrays his ideals for Chinese investments and Western development aid with more strings attached than a marionette theater.

Fela would have refused this Grammy.

Or no, worse. He would have seized the podium. He would have used it to roast every executive present, every sponsor, every complicit artist. He would have exposed the hypocrisy. He would have used the Grammy to dismantle the Grammys.

That’s why they only gave him this award now. Because corpses don’t give speeches.

And here’s the most depressing part: in fifty years this will happen again. Then one of the artists we’re ignoring now, Obongjayar, The Cavemen, whoever is still uncomfortable enough, will also get a posthumous Lifetime Achievement Award. And everyone will say: “Finally! Better late than never!” And nobody will wonder why we always wait until artists are dead before we find them safe enough to honor.

The system has won. Not by stopping Fela, they couldn’t do that, no matter how hard they tried. They won by outliving him. By waiting. By being patient. And now they posthumously claim him as part of their narrative.

Looted art behind glass.

Senegal has a stadium. The British Museum reluctantly returns art. Fela has a Grammy. And everyone pretends this means something.

But here’s what it really means: that we’ve created a world where the only safe radical is a dead radical. Where rebellion is celebrated retrospectively but suppressed in the present. Where we honor history and sell the present.

Fela’s Grammy is not a victory for Africa.

It’s proof that Africa has lost.

And the tragic part is: we’re so desperate for Western recognition that we still accept and thank them for this poisoned gift.

“You see, I got them now!”

No, Fela. They’ve got you. Finally. Now that you can’t fight back.

.

Plaats een reactie